Accuracy versus “Truth” in Television

As a young kid I spent a portion of every summer with my father riding around the back roads of the White Mountains region of New Hampshire. As we worked our way along winding roads and through picturesque villages, I was always on the lookout for the roadside historical markers that are omnipresent in New England. One such marker is on Highway 10 outside of Haverhill, and I would make my father stop there at least once a summer. It read:

This rivers’ junction two miles north was the rendezvous for Rogers’ Rangers after their destruction of St. Francis, Quebec, on October 4, 1759. Pursuing Indians and starvation had plagued their retreat and more tragedy awaited here. The expected rescue party bringing food had come and gone. Many Rangers perished and early settlers found their bones along these intervals (est. 1968).

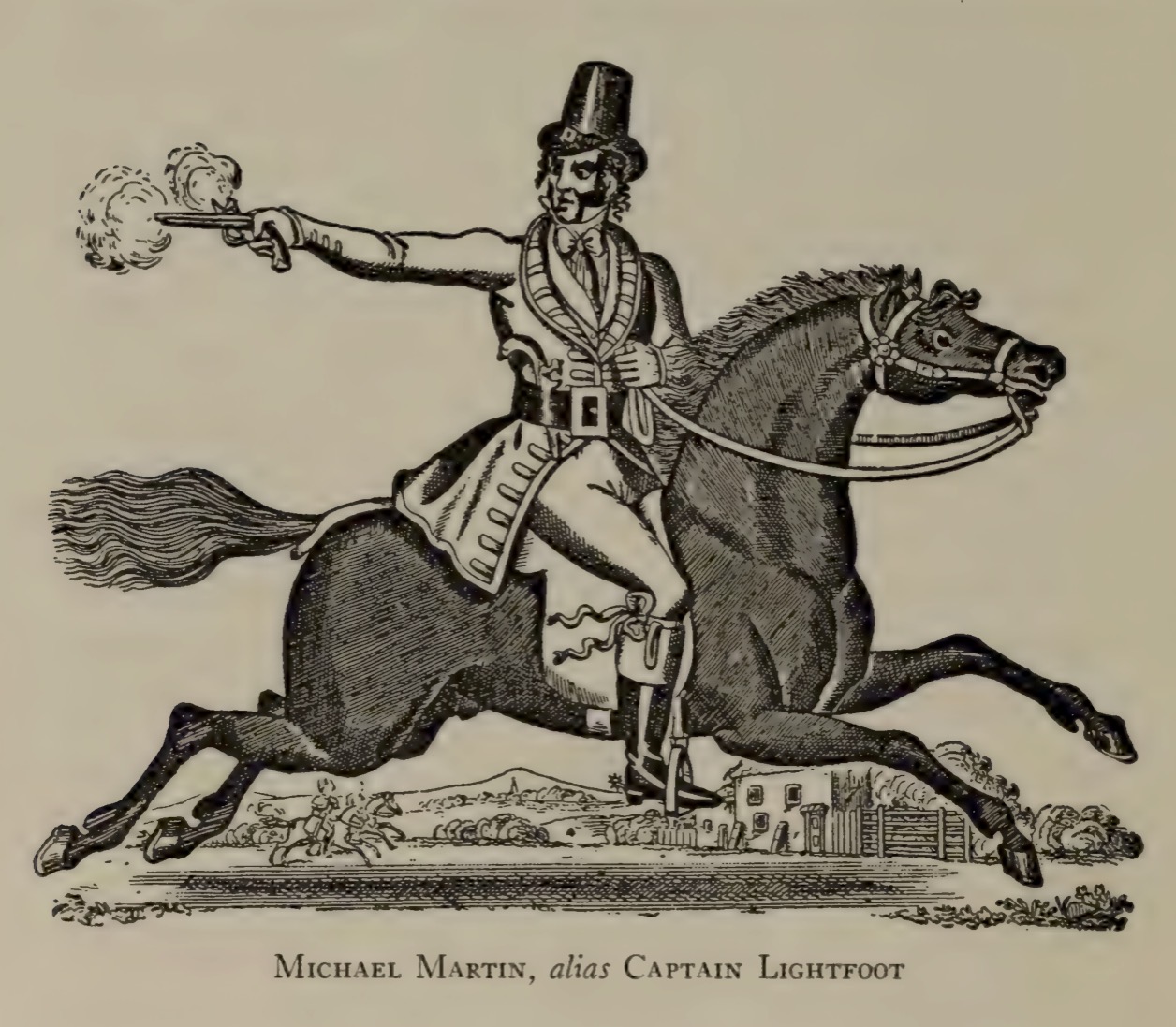

I became obsessed with the history of Rogers’ Rangers and read every book I could find on the topic once I returned to school. Of course, most of the books available in a middle school library followed a mythic narrative of the Rangers as pre-cursors to today’s U.S. Army Rangers. Robert Rogers, the namesake of the company he founded and commanded, helped to develop the tactics used by Rangers to engage in guerrilla warfare against the French in North America. They could cross any terrain, live off the land, and even skate across New England lakes in the winter to raid a French fort. However, my knowledge of Rogers ended with the Seven Years’ War.

This is a different attempt at “truth” that film and television can work toward: raising issues of representation and including marginalized perspectives.

You can imagine my surprise then when I saw Rogers portrayed in the opening scenes of the pilot episode of Turn: Washington’s Spies as a murderous henchman for the British Army. One of Rogers’ Rangers —not the original unit but a new unit called the Queen’s Rangers, recruited largely from New York and Connecticut loyalists—is shown bayonetting colonial soldiers killed in an ambush. Simultaneously, Rogers is shown urinating and talking to his men about how Washington could have had “men and not boys” if he had been willing to pay him. This portrayal caused me to immediately look up the history of Rogers and the Rangers in the American Revolution, and smashed the romantic view I had held from childhood. This example demonstrates the power of television as a form of public pedagogy: this show challenged my own understanding of the Rangers in a matter of moments.

Whether the portrayal of Rogers and the Queen’s Rangers in the opening sequences of Turn is completely accurate is something of a moot point. After all, we cannot expect any film or television program to be fully historically accurate. Nor should we assume that the historical marker itself is accurate, as these markers are often created during particular periods of overt nationalism and are designed and paid for by individuals or groups with particular views. The combination of the two representations of Rogers’ Rangers, however, caused me to explore the record further, look for divergent or competing perspectives on their role in the American Revolution, and in how Rogers and his Rangers were represented in Turn.

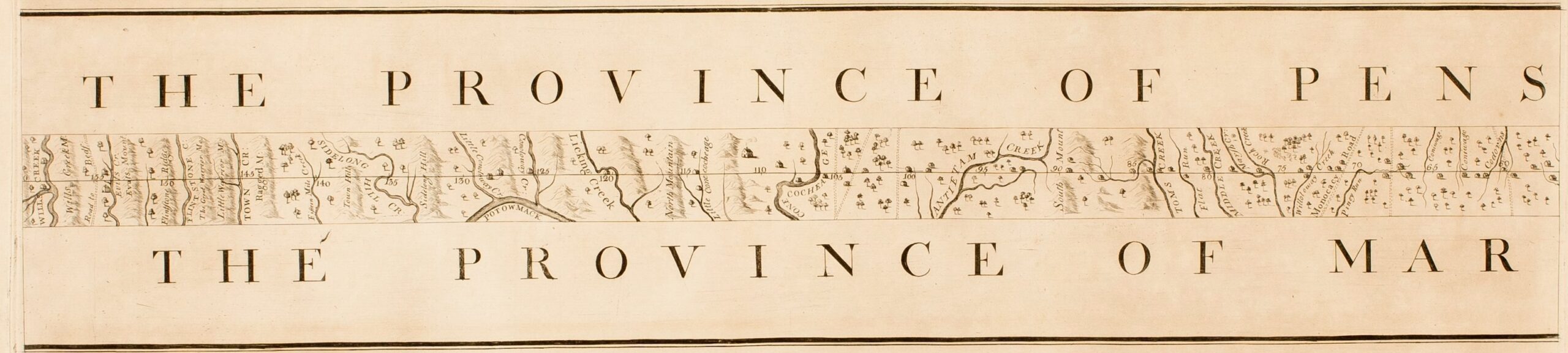

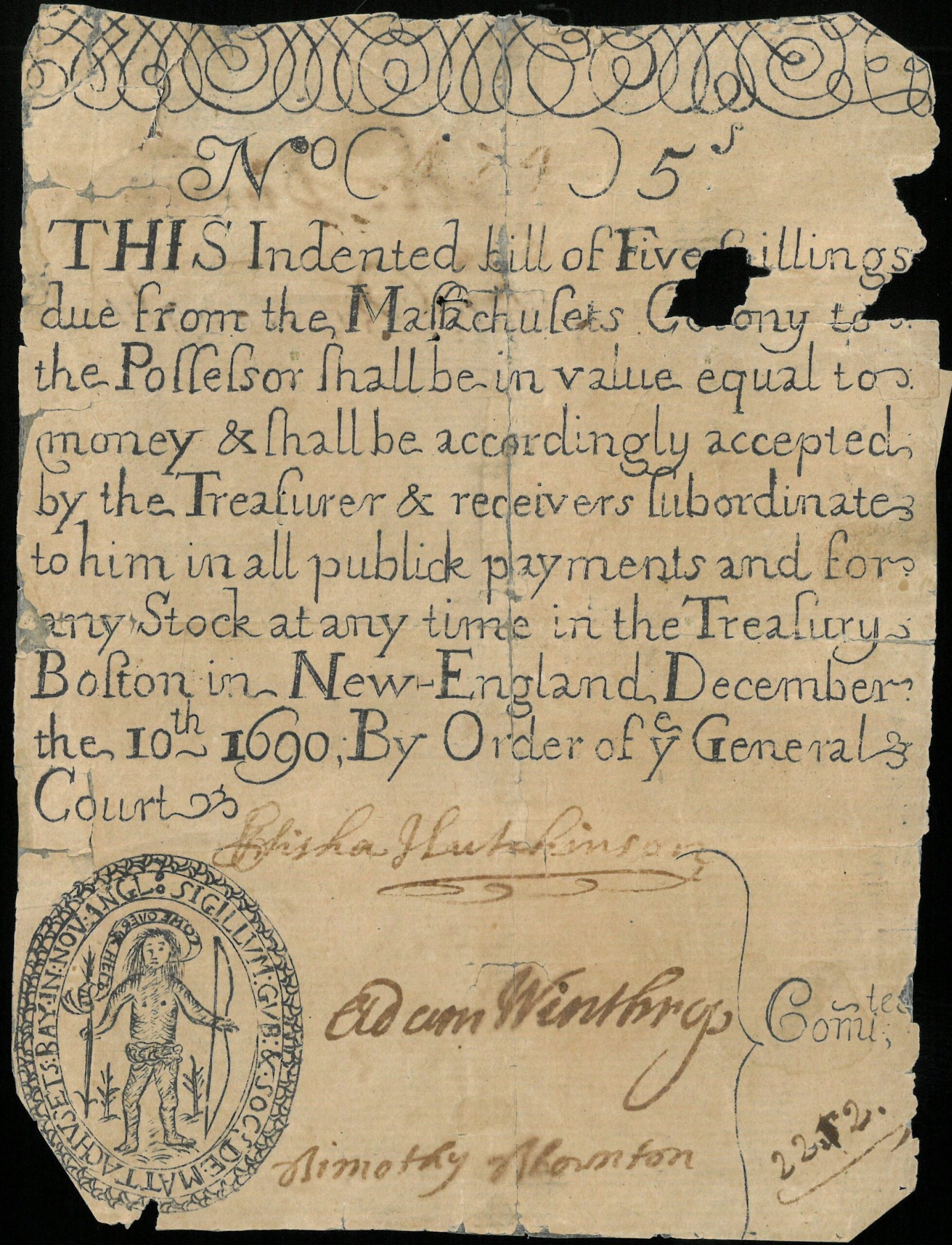

This print of Robert Rogers in a distinctly American setting was one of many published in Europe during the eighteenth century. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

It is this debate over the role of historical accuracy, and more often inaccuracy, in film and television that was the primary basis for a recent panel discussion of academics and Turn producers, writers, and actors. This discussion was held in early February at Phi Beta Kappa Hall on the campus of the College of William & Mary as a preview event to the premiere of the second season of Turn (spring 2015). This location was apt both for the role of the college (Phi Beta Kappa was founded there in 1776) and its many students and alumni (George Washington and Thomas Jefferson included) in the American Revolution, as well as its role as a filming site for the second season of Turn. The panel included four historians and one film studies professor from William & Mary, two executive producers of Turn, the author of the book on which the film was based, who also now contributes as a writer for the show, and the lead actor of the series. Several other actors from the series were also in the audience.

The discussion focused on the role of AMC network executives, the decisions made by the writers in distilling the book Washington’s Spies, on which the series is based, and the decisions made by directors and actors in attempting to translate these written words into the landscape and people of Long Island, New York, circa 1776. Here I use this conversation to explore several core questions about what happens when Hollywood attempts to “do” history, and the ensuing tension between history, memory, and representation in the series.

Accuracy versus Truth

There is a longstanding academic discussion over what happens when history is translated for the big or small screen—be it a Hollywood blockbuster, art house history biopic, or television or web-based serial. Producers, writers, and actors make decisions about how the past should be represented on screen. In the case of Turn, producers and writers need to decide how to interpret and parse Alexander Rose’s 384-page book Washington’s Spies: The Story of America’s First Spy Ring (2006) into multiple ten-episode seasons. They also need to make decisions based on their potential target audience, their budget, and the available filming locations.

If we assume that no historically based film or television series can be completely accurate, then what level of accuracy should be expected? What separates John Adams, HBO’s critically acclaimed mini-series, from Sons of Liberty, the History Channel’s sensationalist tale of Samuel Adams and other Boston patriots? The producers of both series made decisions about which events to highlight in each episode, which characters to include (as audiences can realistically follow only so many), and which parts of the historical record should be kept as accurate as possible and which could be massaged in order to make a better story or to make a story that will make sense on the small screen. Of course, what ends up on the screen is also very dependent on the quality of the source materials the producers, writers, or filmmakers are working with. Rose’s Washington’s Spies, which includes some sensational accounts of espionage, would naturally lend itself to a historical drama with similar elements on the screen.

At the end of the day, the producers need to put together a product that will have an audience, be it the allegedly sophisticated audience of HBO subscribers, or the young male audience that the History Channel covets. We have to remember that the production costs of a film or series require a much broader and advertising-worthy audience than that required by popular history like Rose’s book. For example, at least 2.2 million people watched Turn‘s season one finale—far more than have purchased the book. These concerns over audience, advertising dollars and ticket sales drive much of the decision-making on the set of a historically based production. These worries certainly outweigh a desire to be 100 percent historically accurate. Producers must make decisions that both help make the complex historical stories from the Revolution understandable in forty-four minute episodic chunks, and “sexy” or sensationalist enough to appeal to young and predominantly male viewers whom advertisers crave. These decisions, however, also mean a reduction of historical complexity and at least some degree of tweaking the past to meet the wishes of the intended audience in the present.

The writers, producers, and cast members of Turn discuss historical accuracy and authenticity with scholars at the College of William & Mary in February 2015. Photo by Stephen Salpukas, courtesy of the College of William & Mary.

However, Craig Silverstein, the showrunner of Turn, remarked that producers do go to great lengths to maintain the chronological accuracy of major events in the series, such as the crossing of the Delaware to launch a surprise attack on Hessian soldiers in Trenton, New Jersey, on Christmas Eve, 1776. However, episode 5 of Turn shows that the information leading to that successful surprise attack is the result of the Culper Ring of spies at the center of the series—despite the fact that the Culper Ring was not actively organized until 1778. This decision was made because the writers and producers needed to make multiple seasons for the series that centered on major events in the American Revolution. How does this chronological tampering affect how history is viewed or understood? This is especially important, because this overstatement of the role and effectiveness of the Culper Ring may influence the audience’s understanding of the history of the Revolutionary War.

When a work of history becomes a work of Hollywood, there is almost always a turn to the dramatic that narrows the story and perspectives while also stretching the historical record. Historical drama is not dramatic without the generic staples of romantic love, family conflict, and the like. Major events are used as series focal points, while love interests and conflicts are created for dramatic purpose or to serve as a metaphor, and conflict and storytelling are used to attract and maintain an audience while larger questions about the history of the time are raised. In the case of Turn, the producers attempt to include the perspectives of women and African Americans, as well as Loyalists, that may challenge audiences’ understanding of that period and who the patriots were. Since Rose’s book lacked the love stories and family conflict, they were created by Turn producers and writers. For example, the main character of Abraham Woodhull is shown clashing with his father, a British Loyalist. This conflict did not exist in the historical record, but works in the series as a metaphor for the war—the child (colonies) pulling away from the parent (Great Britain). This kind of adaptation for dramatization is not uncommon. As AMC executive producer Barry Josephson noted, even critically acclaimed historical biopics such as Patton (1970) and Lawrence of Arabia (1962) clung loosely to historical accuracy in order to inject drama. Composite characters are often created to represent the experiences of larger groups of people, and events are added that represent aspects of the war even if they are out of context in the story of the Culper Ring. Josephson explained that the point of making the series is “not about accuracy but about getting the conflict … leading you to the history…[and satisfying] the need to entertain and keep people involved and intrigued.”

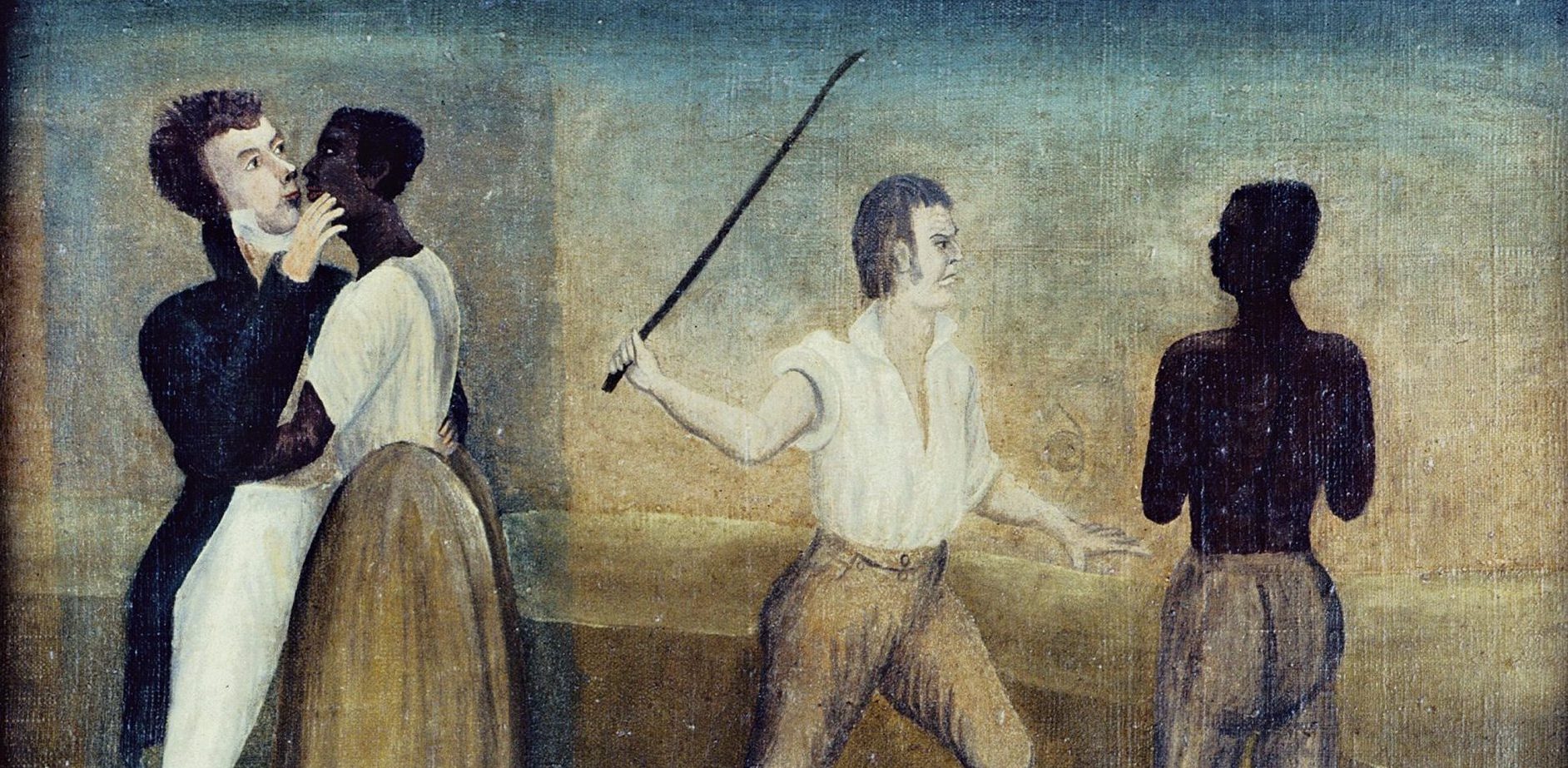

The producers argued that despite this focus on conflict, instead of accuracy, their goal remains a “true” telling of events. Instead of portraying the war as many typical history textbooks do, the producers attempt to show how the war sometimes split families between Loyalists and Patriots, portraying the Revolution as more of a civil war than a revolt against an empire. They also aimed for truth by portraying the complicated history of slavery during the war, even in places like Long Island, New York, where the story is set. For example, episode five features Dunmore’s Proclamation, which ostensibly freed the slaves of those rebelling against Britain, but the show reveals that the British used these same freed slaves as part of their own labor force. Finally, the producers work to more powerfully portray the role of women, both in the Revolution, and in the home, where they could not own property and remained the property of their husbands.

Truth also comes in another form in these kinds of historically based dramas. Producers and directors use cinematic elements and narrative to challenge the audience’s understanding of the past. Was Sam Adams really a smuggler and colonial-era gangster, as portrayed in the History Channel’s Sons of Liberty, or was he the son of liberty and patriot as portrayed in popular history and the namesake of a Boston brewery as he is more commonly known? Maybe. At least these alternative representations of the iconic Adams invite audiences to think about the common representations of the past and question their own understandings. In addition to narrative conventions, cinematic elements such as visual imagery and music are used to portray particular ideas and perspectives. For example, the use of African American spirituals in the Turn scene framing Dunmore’s Proclamation would seem more at home in a Civil War film scene focused on emancipation, or a Civil Rights-era film focused on desegregation. This is because it is essentially a scene from one of these films, right down to the music, singing, sentiments, and imagery of African Americans around a fire at night.

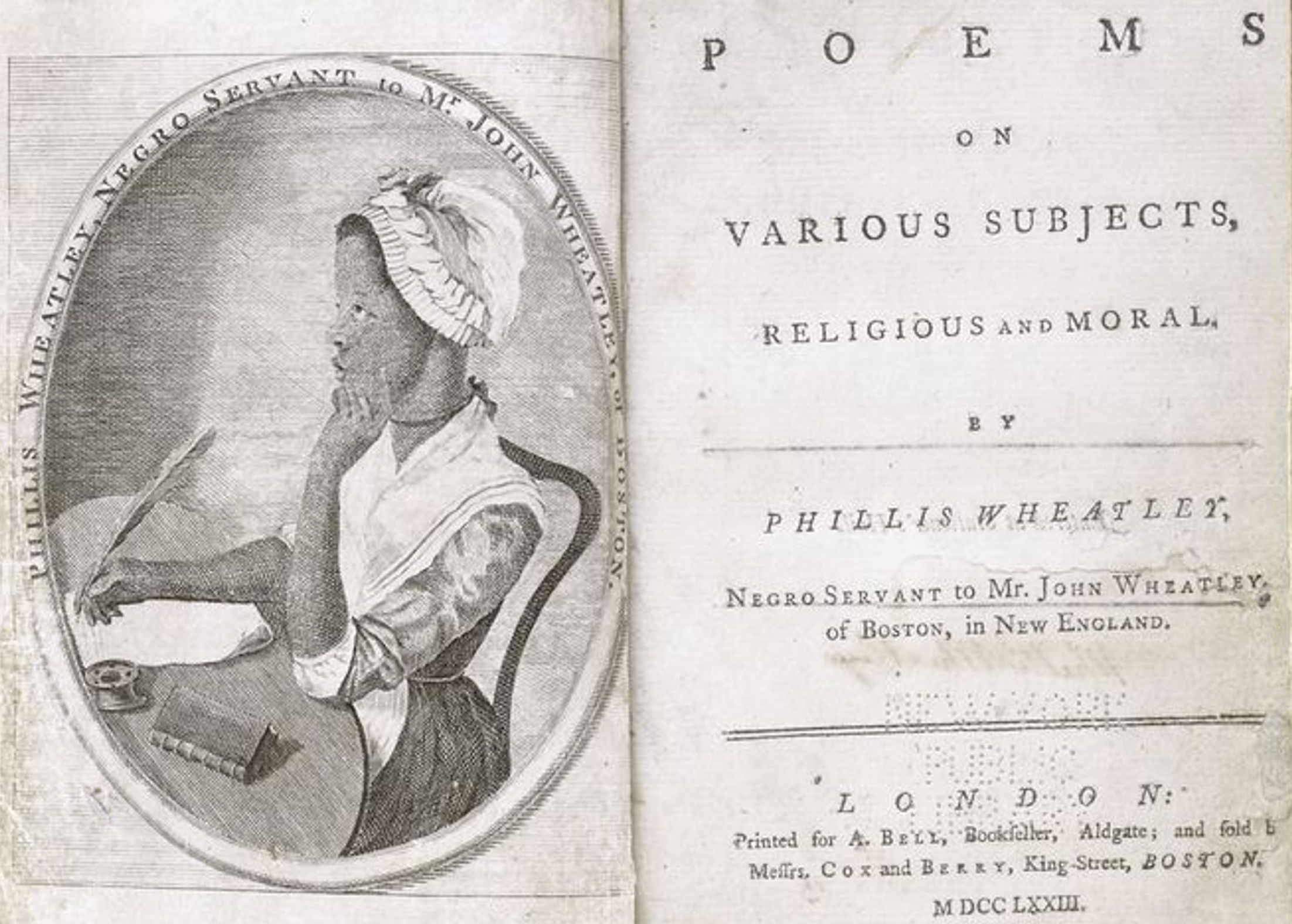

This kind of cinematic device, even if not fully adhering to what the scene would have looked like in Long Island at the time of the proclamation, powerfully challenges the audience to think about the role of slavery during the colonial era and the idea that slavery was prominent in places like Long Island and New York. This is a different attempt at “truth” that film and television can work toward: raising issues of representation and including marginalized perspectives. However, this use of iconic imagery and film convention of the gospel spirituals and freed slaves around a fire also reinforces the narrative in film and popular history of enslaved African Americans who did not actively resist slavery. These scenes also do not recognize the perspectives of African Americans who were not enslaved. Turn does attempt to include these perspectives through some of the black soldiers in Rogers’ company of Rangers, even if in a limited way. These roles in the second season include former enslaved Setauket Black residents on both sides of the conflict, one as a spy for the Culper Ring and another as a soldier in the Queen’s Rangers.

‘We care a lot more than other shows, but…’

Rose, the historian and now screenwriter for the show, and Silverstein provided honest and detailed rationales for their changes in the stories related to the Culper Ring and what they are sure to portray accurately. As Rose explained, they go for “authenticity and genuineness” over perfect accuracy, focusing on whether the scenes feel accurate rather than the minute historical details. This emphasis on the feel of each scene is done in part to help the audience make sense of the narrative and perspectives in the show. The writers want to make the stories in the series as relevant as they can and, embracing a perspective championed by social historians, show “real situations that confronted real people at the time,” Rose said, even while erring “toward drama.” They also felt the need to change aspects of the story in order to make it more understandable for the audience. For example, at the beginning of the series, they decided to portray Redcoat regulars in the town of Setauket, though the historical record shows the town was guarded by a Loyalist regiment.

In this case, Silverstein explained, writers thought that showing Loyalist troops in Setauket might be too confusing for the audience at the beginning. Turn does include a more accurate portrayal of the British forces, which included Canadians, colonial Loyalists, Hessians, and mercenaries such as the Rangers, later in the first season. This decision to represent the soldiers in Setauket in easily recognizable British uniforms reflects a key issue with history film and television programs: given the highly visual nature of the medium, iconic images and signifiers such as the British Army’s red uniforms are used to help the audience easily see whose side they should take. To the producers, truth is the ability to translate the larger themes of the story clearly to the target audience—which is broader than the audience for the book—and aligns with the need to help this audience easily understand the story.

What AMC producers found in Rose’s book was a story that they felt would appeal to today’s audience through an engaging narrative, filled with spies and spycraft, set in the relatively well-known context of the American Revolution, and with some easily recognizable characters such as George Washington and Benedict Arnold. When asked why AMC found the project appealing, Josephson said he saw the story of the Culper Ring as “well preserved,” “complicated,” but not well known. It also portrayed an offbeat, behind-the-front-lines perspective on the Revolution that fit their budget, as they “couldn’t afford the battles.” The AMC funding formula means taking risks on projects like Turn, but without the budgets of HBO productions like Game of Thrones or the John Adams mini-series. This smaller pocketbook means that any battle scenes in Turn include far fewer soldiers on the screen than actually fought on the battlefield.

Cindy Hahamovitch, a historian and moderator of the panel, noted that she found this social history perspective to be particularly compelling. She noted that we learn something different about the Revolution when “we tell it from the bottom up.” Another panel historian, Susan Kern, also noted that it was compelling to see stories of “people making complicated choices.” In particular, she noted that Abe and his comrades take actions behind the lines that reflect the divided loyalties among colonists and not just the colonists versus the British. She also noted that it is powerful to show why many colonists supported the British, with roughly ninety percent of Long Island residents supporting the Crown. Rose added that it was also interesting to show how even Loyalists became weary of British soldiers being quartered in their homes and taking their livestock and crops, quipping that as the war dragged on, the British demonstrated Ben Franklin’s aphorism that “guests, like fish, smell after three days.”

Creating Compelling Characters and Sets

You cannot have popular or even compelling historical drama without powerful characters for the audience to love—and to hate. Turn adheres to this formula of creating “good” and “bad” characters much more strongly than it adheres to the historical record. Several of the actors attended the discussion at William & Mary. Jamie Bell, who plays the protagonist, Abraham Woodhull, was on stage and received a raucous reception from the audience. However, the actor Samuel Roukin, who plays antagonist Captain Simcoe, received an even louder mix of cheers and boos. Captain Simcoe, who even in the historical record is presented as a brutal soldier, is also honored with a holiday in Canada. In many ways, his character embodies the powerful roles of perspective and collective memory in history. Would those in Canada, who celebrate Simcoe’s role as lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada and as an abolitionist, have the same reaction to his portrayal in Turn as I had to the portrayal of Rogers? This reminds us that film and television are not only made by someone, but also made for someone—in this case, Turn is made largely for an American audience. Every decision Turn’s writers and producers make is influenced by the historical record, by the art and form of television, and by the need to attract the audience coveted by advertisers. Without this audience of largely young adult males with higher than average education and income, Turn will not likely be renewed for additional seasons.

In addition to helping to attract the desired audience and playing the role of the bad guy, Simcoe is also used as a contrast to the other British officers. The officers portrayed in Turn represent the multiple social classes of the British officer corps as well as the officers’ diverse views on the conflict in the colonies and of the colonists themselves. Simcoe represents the “fire and sword” anti-gentleman officer, while other characters, such as spymaster John Andre, represent upper-class British officers. Yet others, such as the commanding officer in Setauket, Major Hewlett, represent the ideals of the enlightenment. In contrast to Simcoe, Heather Lind, the actor who plays Anna Strong, heroine and Abraham’s love interest, was met with applause at the discussion as she explained her empathy for Revolution-era women after spending days in a corset and an outfit with “a lot of buttons” doing manual labor.

In these depictions, many issues arise when accuracy is sacrificed for audience appeal and drama—especially when it comes to historical attire. Of course, the appearance of people in colonial-era costumes is not out of the norm in Williamsburg, home of Colonial Williamsburg. Hahamovitch remarked that Williamsburg is “the only place in the world where Jamie Bell can wear his costume to the dentist or the store and no one will pay any mind at all.” However, the details of that costume often caused tension on set, with the costumers who were steeped in historical understanding of the period wardrobe coming into conflict with the directors.

For example, Lind described her character’s winter wardrobe—which, if accurate, would have consisted of a pile of blankets. In Turn, however, she is shown wearing a rather fashionable cloak. In a better example of going for “sex appeal” over accuracy, there was apparently a terse discussion over a scene that had Abraham coming out of his house at night. The costumer argued that Bell should be wearing some kind of long nightshirt, while the director wanted Bell “bare chested” and “sexy as hell,” as Silverstein put it, and Bell ended up wearing colonial-esque pajama pants instead. These are the conscious decisions made to create compelling characters for their target audience. The effect is that an audience may have a naïve and romantic view of life in the eighteenth century, a life that includes beautiful people, cleavage, and garments and attitudes likely absent at that time in the colonies.

In addition to creating compelling characters, the writers and director need to fill in the aesthetics of place for each scene. Historian Susan Kern noted that compared to writing history books, when making a TV show, “you need to make a lot more decisions about what everything else should look like in the background—in that world…” The producers explained that this world-building was a major challenge and the reason why much of the filming takes place in locations in Virginia (e.g., Petersburg, Richmond, Williamsburg), with its plentiful historic buildings and settings. Given that the Long Island coast of the Turn era no longer exists, and directors wanted to avoid computer-generated imagery (CGI), they used Shirley Plantation, a historic estate on the James River, as a replacement for a Long Island coastal home.

Their reason for filming on the William & Mary campus was not to depict a colonial-era university but to use the seventeenth-century architecture of the Wren Building as a stand-in for an English palace. A room was needed to serve as King George’s throne room in one of the opening scenes for season two. After scouting various locations, directors settled on filming in the Great Hall of the Wren Building, which is the oldest educational building still in use in the U.S. One of my students, who works as a docent in the building, noted that there was a lot of secrecy when filming was taking place. This may have been in part because a room that normally holds portraits of the three American presidents who attended William & Mary was used as the setting for George III’s throne room, adorned in the scene with CGI-rendered tapestries and decorations fit for a king. It is, of course, quite ironic that a room where separation from King George was likely discussed was used to recreate his throne room. This ability to digitally recreate a setting lends visual authenticity to the production, and thus may lead audiences to believe in the authenticity of the history as well. This is a challenge for the historical profession as the public receives more of its information about the past from visual sources such as Turn and History Channel documentaries than from books.

The many small decisions regarding what characters and settings will look like are a challenge not often faced by historians. As Rose noted, historians often describe what a particular person or site might have looked like but don’t have to describe an entire 360-degree view of a village. The producers of Turn do this for every scene. Rose also explained the daunting task of writing for television. For the current second season, set largely around Philadelphia and involving historical figures such as Benedict Arnold and Peggy Shippen, he had the task of explaining the history and role of Quakers for the audience in one scene. The section on Quakers in his book is over five pages, but in the script, he was allowed two lines and “a look” to portray the relevant history. This leads to even more simplification of Quaker culture in a subsequent episode, as Peggy Shippen tells her lover that they can be married by just saying so—a slight misrepresentation since Quakers do not require a minister to officiate a wedding but do need a congregation to be present. This is an example of the reductive nature of visual representations of history in film and television.

Rose also noted that season two is much more of a “straight spy story” than season one and is filled with intrigue and more recognizable characters such as Arnold and George Washington. Washington’s role was actually diminished in season one at the request of the AMC producers. These genre decisions— whether a history film should be a Western (American Sniper, Zulu, We were Soldiers) or some other genre (such as a courtroom drama)—help a broad audience easily understand what is occurring on screen. If you make a Western, audiences know to expect a good guy, a bad guy and a conflict in a particular, often remote or exotic, setting. In American Sniper, there is a good guy in Chris Kyle (white hat/baseball cap) and bad guy in Moustafa (black hat/head scarf) in the exotic—at least for American audiences— Iraqi cityscape. By casting Turn as a spy story, the audience similarly has recognizable conventions allowing them to easily follow the story, know what to expect, and know whom to root for and against. These conventions include betrayals, fear of being discovered, the use of codes, gadgets and spycraft, and the role of intelligence gathering in creating chaos or triumph. Stories set in history are usually grounded in the genre that fits best, including war films, Westerns, spy dramas, or biopics.

What Was Not Discussed: The Present in the Past

When asked “How risky was it to make a show that was not about zombies?” Silverstein responded that the producers had some initial problems selling the idea for Turn. Fox initially turned them down, thinking that the international appeal and sales would be lacking. But AMC decided to give it a shot. According to the panel, AMC did not want the writing staff to go beyond the archetypes that already existed in the stories or to make it too heroic. In fact, they wanted Washington’s role to be diminished early in the series in order for other characters to develop and for a more social history perspective to bloom. What they did not discuss, however, was how the events of the past fifteen years had influenced the stories and portrayals in season one—nor did any of the historians on the panel make this connection.

But those connections are undeniably present. Starting in the pilot episode, echoes of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are present on the screen, in the dialogue, and in the narrative. Starting with the text introducing the first episode, patriots are described as “insurgents.”

Autumn 1776. Insurgents have declared war against the Crown. Following a successful naval landing, His Majesty’s Army has forced Washington’s rebels into the wilderness. New York City serves as military base of operations for the British. The Loyalists of nearby Long Island keep vigilant watch out for sympathizers, and spies (Original air date April 6, 2014, AMC).

This is the first of numerous language and visual signifiers of the war on terror. As the innovative American officer Benjamin Tallmadge is building his spy network, his operatives are shown using a colonial method of waterboarding as they attempt to make Abraham talk by dunking his head in a bucket of water. This convinces Tallmadge and others from the area that Abraham’s sympathies are with the Continentals. Later, Tallmadge is involved in a sort of rendition act as Simcoe, captured in an ambush of a British company, is held in a secret location and tortured to try to extract information. These scenes are followed by a debate over intelligence strategies with Tallmadge’s commanding officer, reflecting many of the debates over the role of the CIA and NSA in the present-day conflict of security versus civil liberty. As in the present day, the innovative and risky intelligence operations rule the day and the risks are seen as necessary for national security. Thus Washington himself orders a new intelligence network and unit to be formed with Tallmadge as its commanding officer and Abraham, who is to be known by the pseudonym Mr. Culpeper (later Culper), as its primary asset.

Here, as in other works of historical fiction, we learn more about the issues, ideas, and values of the time and place of production and those who produced it than the historical event or characters being portrayed. In season two, the intrigue focuses on the most notorious of Revolutionary betrayals, that of Benedict Arnold, and his relationship with Peggy Shippen. Shippen, whom Silverstein described as the Paris Hilton of Revolutionary-era Philadelphia, provides a dose of drama from the early episodes of the second season. She is portrayed as a socialite with more modern attitudes toward sex, relationships, and the desire for power than a young eighteenth-century Quaker woman would have had—even one viewed as scandalous in the historical record. In one scene, the temptress Shippen has her own wardrobe revision as she is shown waiting—topless, with only a petticoat on—for British spymaster Major Andre in his bedroom. As the season moves on we will undoubtedly see her role as Benedict Arnold’s future wife and accomplice in betrayal emerge. Season two is supposed to bring the story up to the moment when the real Culper Ring becomes most active, 1778 (and the show has just been renewed for a third season).

For viewers and scholars alike, it is important to ask if and how historical accuracy is important. Perhaps, however, it is more pertinent to think about any television representation of the past in terms of the nature of the inaccuracies as well as the purpose of those inaccuracies. It may be more important for us to consider and reflect upon the larger questions about the past that the producers (e.g., director, writer, production company) hope to pose through a film or television show. Further, we should ask ourselves what the representation tells us about both the past and the present, as films reflect the social and political views of the time of production as much as they attempt to tell a story about the past.

If Turn is a form of public pedagogy, what is the resulting lesson? How does this lesson reinforce the nationalistic narrative about the Revolutionary era and the Founding Fathers that most of us received in our schooling and in our visits to historic sites? What does it challenge us to think about differently? These questions may be more important than whether all of the events in the film fit the chronological order in the historical record, or whether all aspects of the representation of clothing and other details are accurate. In the end, we must also remember that while shows like Turn and films like Selma may be seen as historical accounts by some, they are intended to be entertainment that uses history as its source and not its script.

We should encourage people to critique accuracy and inaccuracy, but also remember that we should not hold these films and television programs to the same standard we would a work of academic history. We should also discuss what the director’s motivations might have been for decisions that make the work less accurate, and the effect those may have on how we view the past. It is only when we reach this level of critical thought and reflection that we begin to understand the overall issues in historical representation, collective memory, and how the past is presented and re-presented through media such as the moving image. The hope is that Turn and other historically set films and television programs serve as a starting point for inquiry into the historical record, as the portrayal of Rogers did for me, and not as a substitute for the historical record.

The panel:

Barry Josephson, executive producer of Turn: Washington’s Spies

Craig Silverstein, executive producer/showrunner of Turn: Washington’s Spies

Alexander Rose, author of the book Washington’s Spies

Jamie Bell, actor in Turn: Washington’s Spies

Susan Kern, executive director of the Historic Campus and history professor

Arthur Knight, associate professor, American Studies, English, and Film & Media Studies

Karin Wulf, director of the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture

Joshua Piker, editor of the William & Mary Quarterly and history professor

Moderated by Class of ’38 Professor of History and Chair Cindy Hahamovitch

This article originally appeared in issue 15.3.5 (July, 2015).

Jeremy Stoddard is associate professor of education and an affiliated faculty member in the Film & Media Studies program at the College of William & Mary. His research focuses on the role of media in teaching and learning history and politics in democratic education. His research has appeared in interdisciplinary journals such as Film & History and The History Teacher, and in co-authored books Teaching History with Film (2010) and Teaching History with Museums (2011).