Almost one million people flock to the National Archives on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., each year to see, among other things, the United States Constitution. The National Constitution Center (NCC), set to open in Philadelphia on July 4, 2003, expects one million annually to troop through its doors as well. But reverence does not imply knowledge. Despite the high interest in the document that these attendance numbers might suggest, public opinion research and visitor studies conducted over the last two decades demonstrate that the Constitution remains, as Michael Kammen once wrote, “swathed in pride yet obscured by indifference.” Many National Archives visitors whom I interviewed last summer saw their trip to D.C. as a pilgrimage to a sacred shrine. Yet when queried about the particulars of the Constitution, many people cannot accurately quote the document or determine its function.

Despite the Constitution’s famed Preamble establishing “the people” as the sovereign power from which all governmental authority derives, the American public came rather late to a first-hand knowledge of the document. Delegates at the 1787 Constitutional Convention maintained strict secrecy during the proceedings. Windows were shuttered; a ban was imposed upon speaking of the proceedings outside of the room. Local papers gave little hint of momentous happenings in the city as they continued to be fascinated with the “Male child of the most extraordinary size ever known,” which they labeled “the greatest phenenomom [sic] of the present age.”

After the proceedings, beginning with the Pennsylvania Packet on September 19, 1787, newspapers did print the Constitution and the public debate that ensued over the next two years of the ratification process. In 1796, a school text entitled A Plain Political Catechism also was published. Few other books or pamphlets, however, were published for the general public to explain the Constitution in the early years of the nation. By the 1850s, statesmen were lamenting the lack of common knowledge about the document’s contents.

But while public familiarity with the Constitution languished, reverence for the document as the foundation of the American system grew. Beginning in 1916, a movement to allow the public greater access to the Constitution–both the document itself and its contents–began with a suggestion to mark September 17 as Constitution Day. The movement gained momentum during the next decade as a way to fight socialism and communism. By the 1920s, the Constitution had become as sacred a text as the Declaration of Independence, if not more so.

This interest eventually led to a more public presentation of the Constitution as physical artifact. The general public had not seen the document much during its first hundred years. Moved from one storage facility to another, it was the property of the State Department. In 1920, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution finally were put on display together. In 1921 President Harding had the documents transferred from the State Department to the Library of Congress where a “shrine” was dedicated in 1924 in a second floor display area. With the advent of film, educational materials helped to spread images of the Constitution’s likeness–if not knowledge of the document’s contents–to students and adults.

Despite these measures, by the last half of the twentieth century, popular knowledge of the Constitution, its history and its principles, was poor. A 1943 National Opinion Research Center study showed that only 23 percent of respondents could correctly name some of the rights protected by the Bill of Rights. In 1947, the Gallup Poll noted that 41 percent had no knowledge of the contents of the Bill of Rights. On the bicentennial of the Constitution in 1987, a study by the College of Education at the University of Houston reported that 46 percent of those queried did not know that the Constitution created a system of government.

In the most recent NCC poll, conducted by Minda Borun in November 2001, two-thirds of respondents could not identify the Constitution as the outline for U.S. government, while less than one-fourth could correctly pick three items in the Constitution from a list of six choices. People seemed to recognize their ignorance. In another NCC study, only 12 percent of respondents claimed to know “a great deal” about the Constitution, with others avoiding taking the survey out of self-professed shame.

Two core areas of confusion reign. The first one is that many people mix the elements of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. According to the 2001 NCC study, 71 percent of those surveyed thought the Constitution, rather than the Declaration, guaranteed citizens “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” And, in a similar poll in 1997, over a third of respondents also identified “all men are created equal” as a quote from the Bill of Rights.

The second area of confusion concerns the relationship between the Bill of Rights and the Constitution itself. One curriculum writer under contract for the NCC stated, before corrected, that the Constitution had a preamble and a bill of rights, leaving out the central articles that create the foundation of the system. No wonder that students, therefore, are especially confused.

Teachers at the Delaware Council of Social Studies 2001 Conference identified the Bill of Rights as the one part of the Constitution that students knew. At the fifth grade level, students simply knew the Bill of Rights existed. By middle school, the students knew one part of the First Amendment–the freedom of speech. By high school, they were familiar with almost all ten of the amendments, but they still were not highly cognizant of the rest of the document. Teachers attributed this phenomenon to the fact that the Bill of Rights was the only part of the Constitution that seemed relevant to the students in their daily lives.

Lack of obvious relevance of the document to the daily life of ordinary people is one reason we seem to retain so little factual knowledge about the Constitution. In The Presence of the Past, authors Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen conclude that people’s sense of history is personal. “Most Americans simply do not recognize themselves and their families in a distant narrative that . . . equates our national past with the history of the nation state,” they write. Broad national movements matter most when they touch the life of a family member or close friend. Participants in an NCC program where people were asked to sign the Constitution echoed this conclusion, finding little connection between the document and their personal lives. Eighteen percent, even after learning about the document in the program, said that it held no relevance for them. Instead, respect was the emotion they expressed.

In fact, reverence for the document is key to how people today think of the Constitution. As a sacred text in the United States, the Constitution is something most adults believe that children should learn about in school. About one-third of the visitors to the National Archives in Washington, D.C., on July 2, 2001, came to the Archives with at least one child under twelve, many having made the trip in order to show the documents on display to their child or even because the child, having studied the Constitution in school, wanted to see it. As one woman from California said, her “children wanted to come to D.C.” and she decided they should “see the document.” Indeed, many deemed the visit important enough to wait with their children nearly an hour on a hot, steamy afternoon. As a parent of a sixth grader put it, seeing the Constitution “reinforces a feeling of being American.”

Once people cleared the metal detectors into the Archives, they entered the dark and very cold interior only to encounter more lines. A security guard informed them that they could go around the perimeter of the rotunda and see other documents like the Magna Carta on their way, or “fast-track” to see only the Declaration and Constitution. About half chose the straight and narrow route to the American scriptures, while a quarter of the visitors waiting in line to enter the building had said they came specifically to see the Constitution. It is a “national treasure,” “the foundation of the country,” as some waiting to see it commented. No one other document received as many mentions as the motivating factor for the visit.

Thirteen percent of those exiting the Archives also said they had come specifically to see that document. The discrepancy in numbers suggests that the Constitution has good name recall. When asked to name something housed in the National Archives, visitors could remember the Constitution. The discrepancy also may suggest that when visitors have seen all of the exhibits, it is harder to recall one specific reason for the visit. After leaving the Archives, as many people said their visit was to see the Declaration as the Constitution.

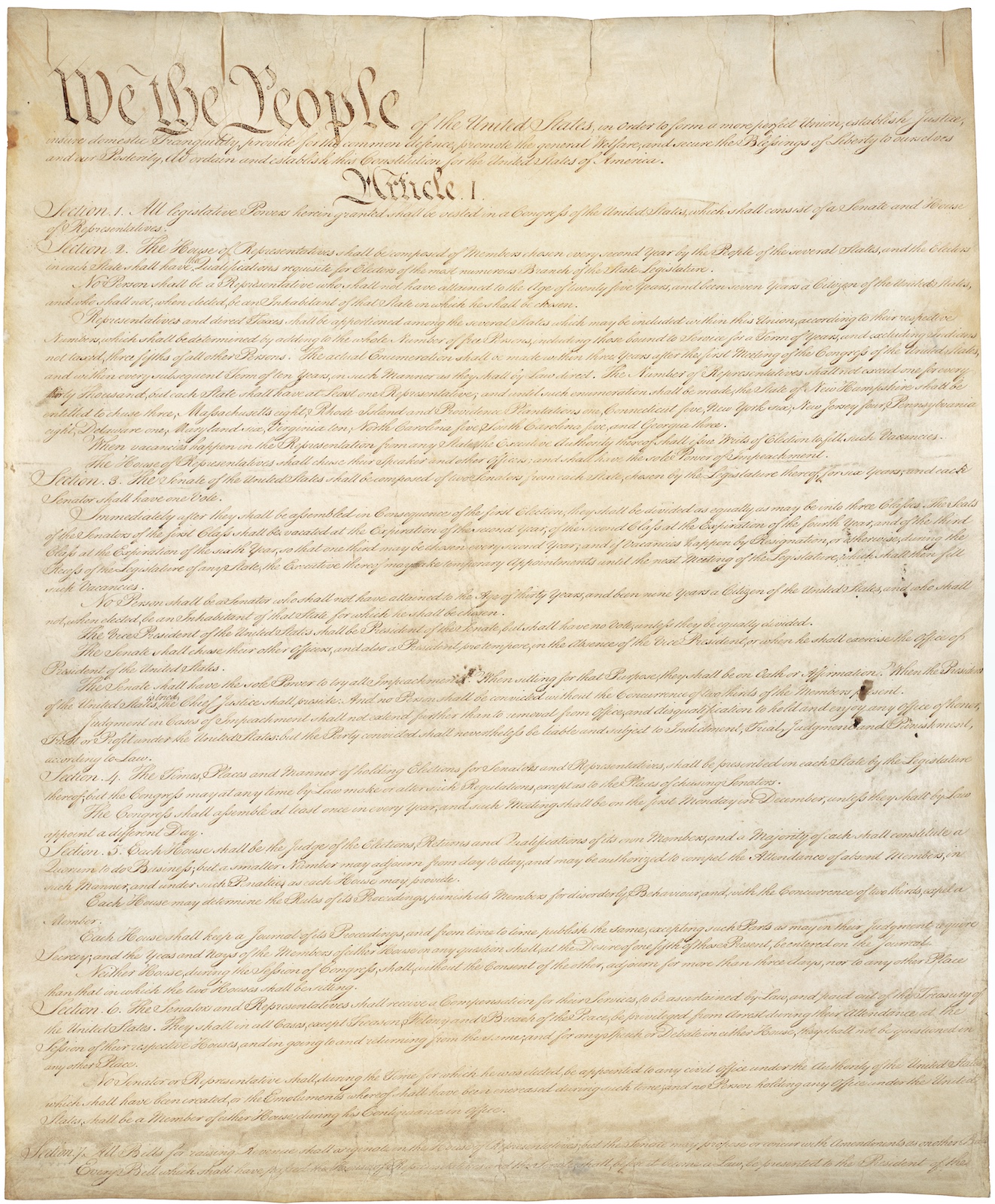

The item that people noted as most interesting about the Constitution also differed between pre- and postvisit. Before seeing the Constitution, over one-third of the people I talked to said they were most interested in the history behind the document and its significance to American history. Fewer than one in five expressed interest in the physical nature of the object itself. After viewing the Constitution, however, half of the visitors commented on the physical nature of the document: its preservation and legibility.

The signatures at the end of the document (fig. 2) fascinated visitors. One elderly man was excited to see that one signer had his last name. Others were frustrated by the darkness of the room and the illegibility of the writing, commenting that the text “was hard to see.” Yet others focused on the act of signing itself and the meaning of such an act. “What must it have been like to be a founder?” one visitor wondered.

The act of signing one’s name indicated a commitment. In the “signing” program mentioned above, almost half of the respondents indicated that signing was “a public endorsement of a set of beliefs.” One participant indicated his signature meant, “I agree with what it says.” Others went beyond content to personal affirmation, reenacting the role of Founder. “It’s a pledge–reminds us of where we stand.” “I felt like, when I was signing it, I was making a decision.”

The legibility of the framers’ signatures also made viewers think about the preservation of the document. Perhaps because the National Archives survey was done the weekend before the building closed for two years of renovations, visitors were quite observant of the lighting conditions, the quality of the paper, and overall state of preservation of the Constitution. Most felt the document was in poor condition, but a few commented on how thrilled they were that something of its age still existed, though the Constitution was far from the oldest document on view.

The experience of seeing the “real thing” was the most common postvisit response I heard during the Archives survey. “It’s cool to see the original document,” offered one viewer. “It fills me with a great sense of meaning.” In other museums in which I have worked, I also have heard again and again people comment on the “real-ness” of the artifact or the environment. Merely to be in the presence of what is considered an authentic relic of the past is a personal connection, a way to engage with history, even if the engagement consists only of viewing.

As I observed visitors in front of the Constitution in the Archives’ exhibit, I noted that half in fact did nothing but look–and then for an average of thirteen seconds. Out of that quick looking, however, came strong responses, from a cryptic “you don’t want to know,” to an excited “amazing!” When asked the most interesting thing about the Constitution, one person replied reverently that “just being in its presence” was awe inspiring.

Reverence incorporates honor, respect, deference, and veneration. But also distance. The object of reverence is a faraway thing, part of the then and there, rather than the here and now. Perhaps this is why some 91 percent of those surveyed by the NCC in 1997 said the Constitution is important, while just over 10 percent claimed to know much about it.

If reverence equals distance, must it also equate with inaction? Report after report documents an alarming lack of civic involvement by many American adults. For instance, in the last presidential election, only 53 percent of those eligible voted. Despite the perceived importance of the Constitution and the emotional impact that viewing the “real thing” made on those I spoke with last July, an understanding of the connection of the document to daily life and of the personal responsibility to uphold the Constitution is lacking. One signing program participant summed up the task ahead for institutions like the National Archives and NCC: “People need to know about this . . . it’s part of being American.”

Further reading: Background on the writing of the Constitution can be found in Catherine Drinker Bowen, Miracle in Philadelphia (Boston, 1966) and Gordon S. Wood, The American Revolution: A History (New York, 2002). For a more detailed history, see Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776-1787 (Chapel Hill, 1969). The following books discuss Americans’ understanding of history in general as well as the Constitution specifically: Michael Kammen, A Machine That Would Go Of Itself: The Constitution in American Culture (New York, 1986) and Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen, The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life (New York, 1998). In addition, the following works explore visitors’ desire for “real” objects and their definitions of and abilities for interactivity: Amber Combs, “Why Do They Come? Listening to Visitors at a Decorative Arts Museum,” Curator 42/3 (July 1999): 186-97, Lisa C. Roberts, From Knowledge to Narrative: Educators and the Changing Museum (Washington, D.C., 1997), Beth A. Twiss-Garrity, “Children as Museum Visitors,” Current Trends in Audience Research and Evaluation 13 (May 2000): 71-81, and Stephen Pinker, How the Mind Works (New York, 1977). The visitor statistics come from “What Americans Don’t Know about the Constitution,” The College of Education/Collaboration for Learning and Leading, University of Houston; Suzanne Soule, “We the People . . . The Citizen and the Constitution: Knowledge of and Support for Democratic Institutions and Processes by Participating Students,” Center for Civic Education; “Startling Lack of Constitutional Knowledge Revealed in First-Ever National Poll,” The National Constitution Center Applied Research and Consulting LLC, NCC, “I Signed the Constitution Report,” National Constitution Center (1999); Minda Borun, “National Constitution Center Survey,” National Constitution Center, 2001, and data generated by the author and intern Jennifer Phillips while surveying visitors on July 2, 2001, at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. A review of 1787 Philadelphia newspapers is found in Martha Crary Halpern, “Laurel Hall and the Year 1787” for the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Philadelphia, 1987).

This article originally appeared in issue 2.4 (July, 2002).

Beth A. Twiss-Garrity is vice president, Interpretation for the National Constitution Center, opening July 4, 2003, on Philadelphia’s Independence Mall. Her publications include “Material Culture as Text: Review and Reform of the Literacy Model for Interpretation” in American Material Culture: The Shape of the Field (Winterthur, Del., 1997); and “Listening to Our Visitors’ Voices” in Old Collections, New Audiences: Decorative Arts and Visitor Experience for the 21st Century (Dearborn, Mich., 2000).