The Literary Paradises of Hurston and Bartram in a High School Curriculum

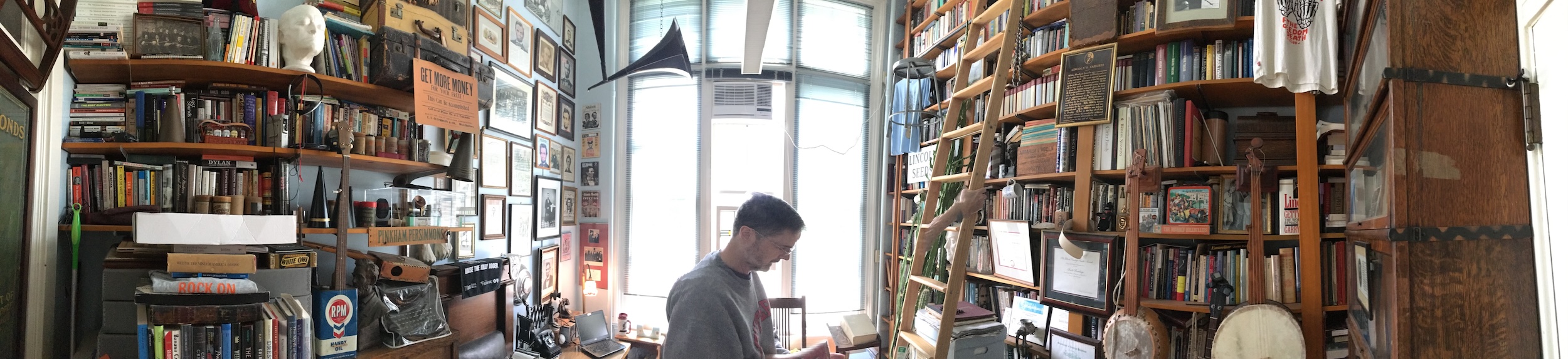

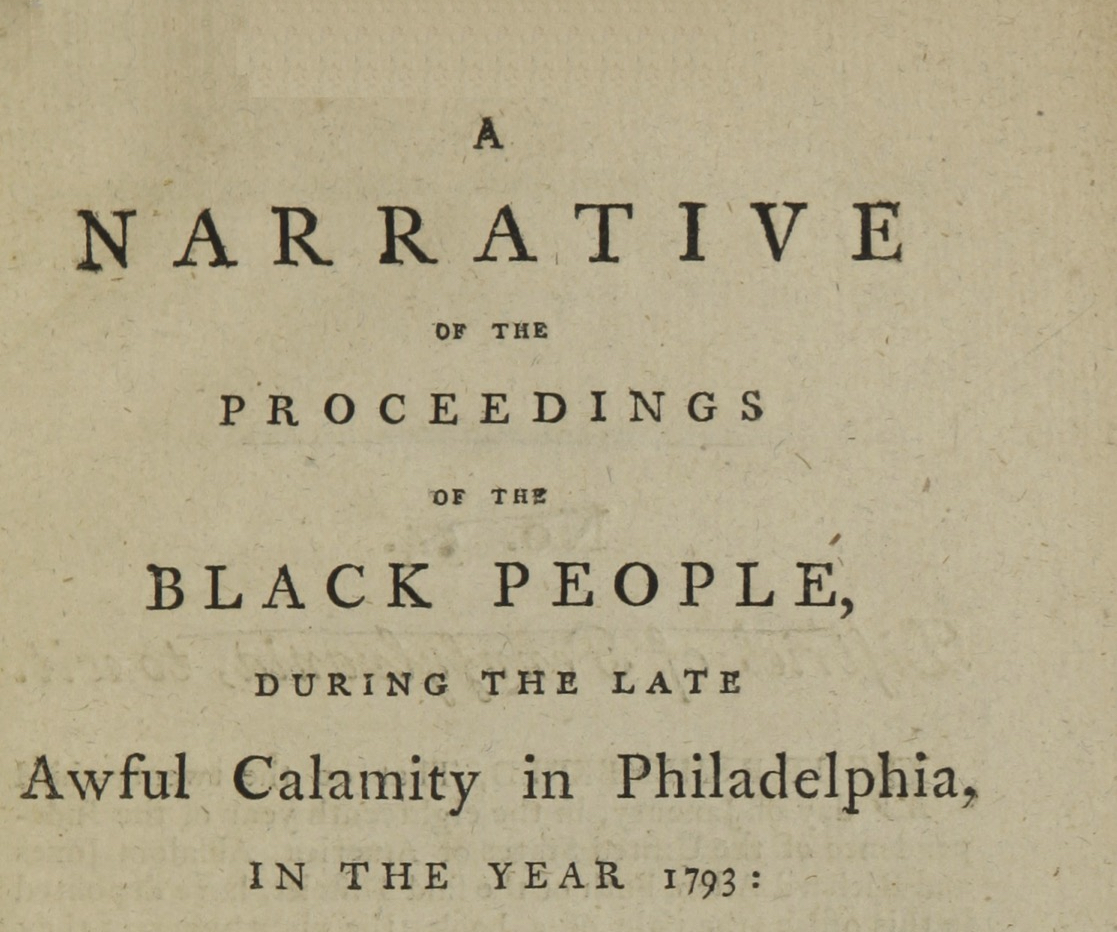

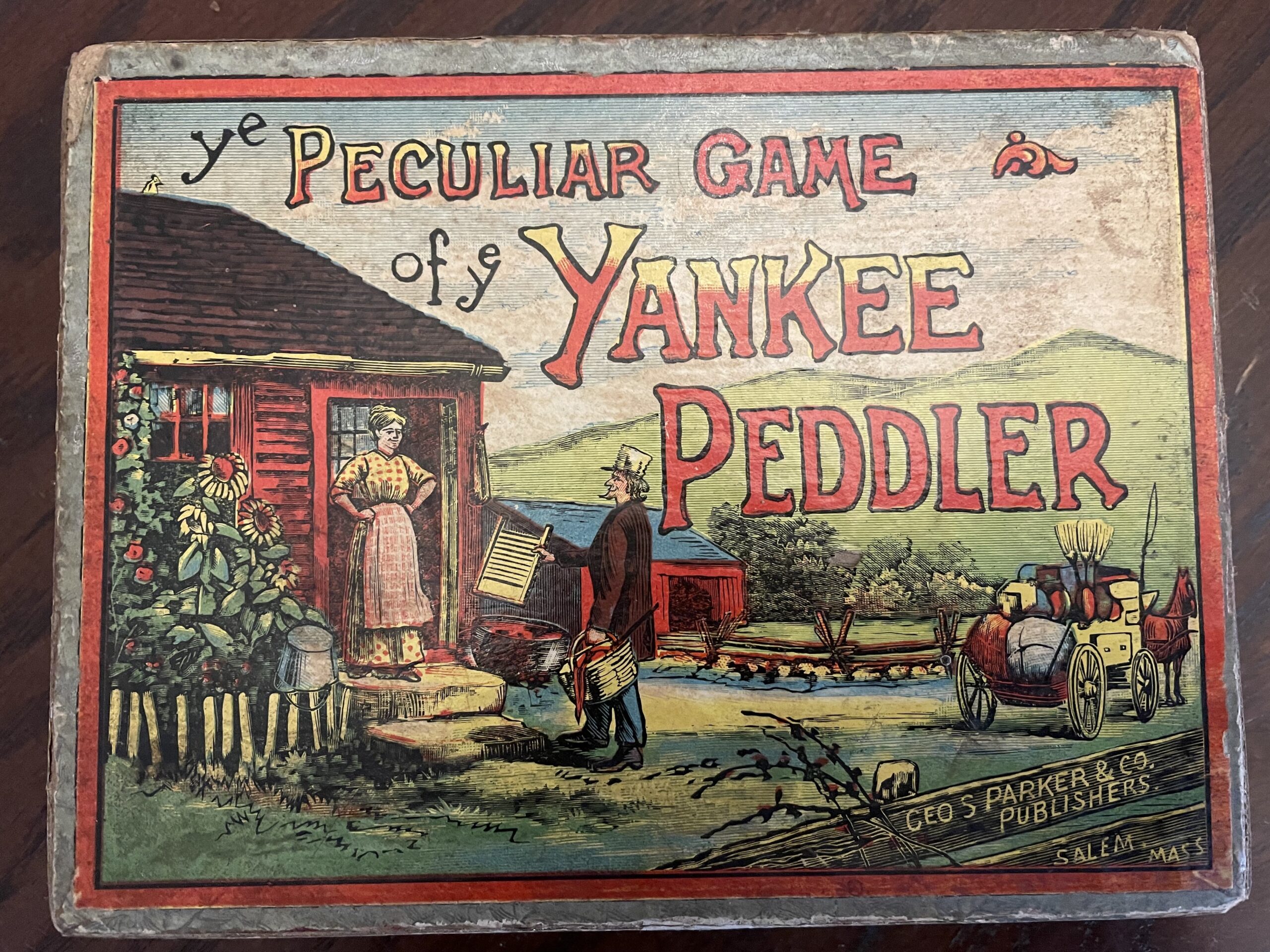

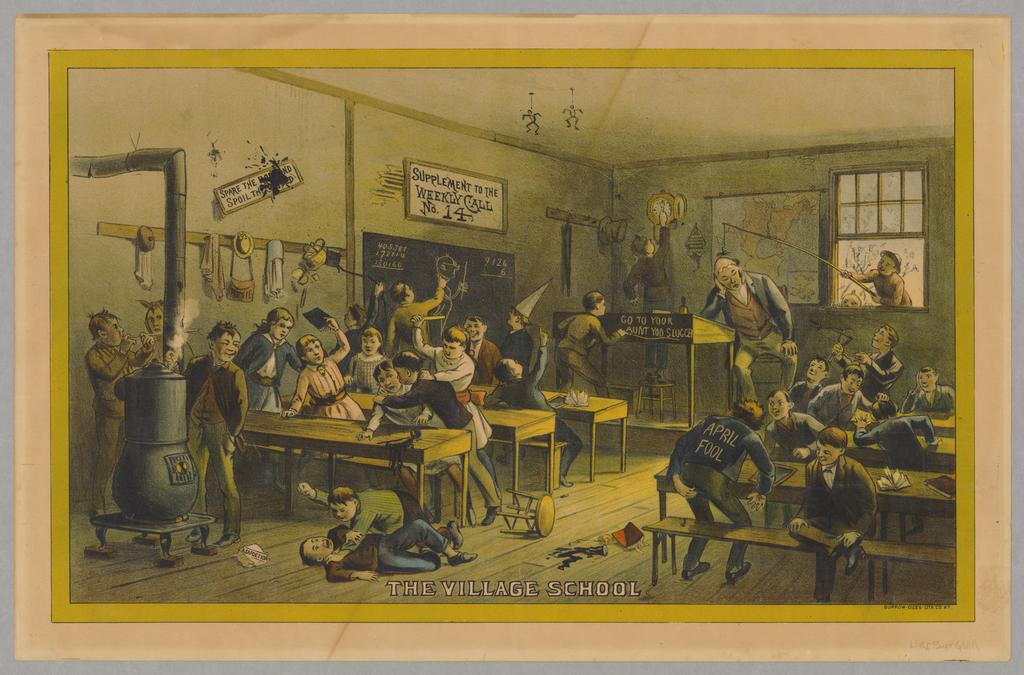

Early American literature is not commonly taught at the high school level. There are many reasons for this: diction is florid, page counts are high, novels are nonexistent, and a more painless nod to the colonial period is easily managed with a study of The Scarlet Letter or The Crucible. If the typical goal of high school literature classes is to inculcate a love of reading in students and to expose students to writing worth mimicking, then the most prudent course is to cleave to the latter half of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. During my years teaching some of the most popular curriculum standards, though, I have found that opportunities abound to incorporate earlier texts.The Great Gatsby cries out for excerpts from Ben Franklin’s journals, and the references that Anne Petry makes to the Junto in her novel The Street do as well. Study of Ralph Ellison requires supplementary readings in the Transcendentalists to help unpack allusions to Emerson and the Golden Ball. Even one Brit Lit high school stand-by, Jude the Obscure, requires reference to an early American antecedent: Thomas Hardy’s model for the Bible altered and improved by the iconoclastic Sue Brideshead was surely modeled on Thomas Jefferson’s Life of Jesus of Nazareth.

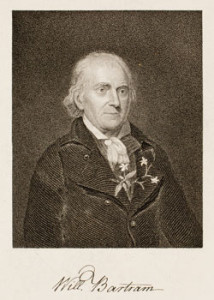

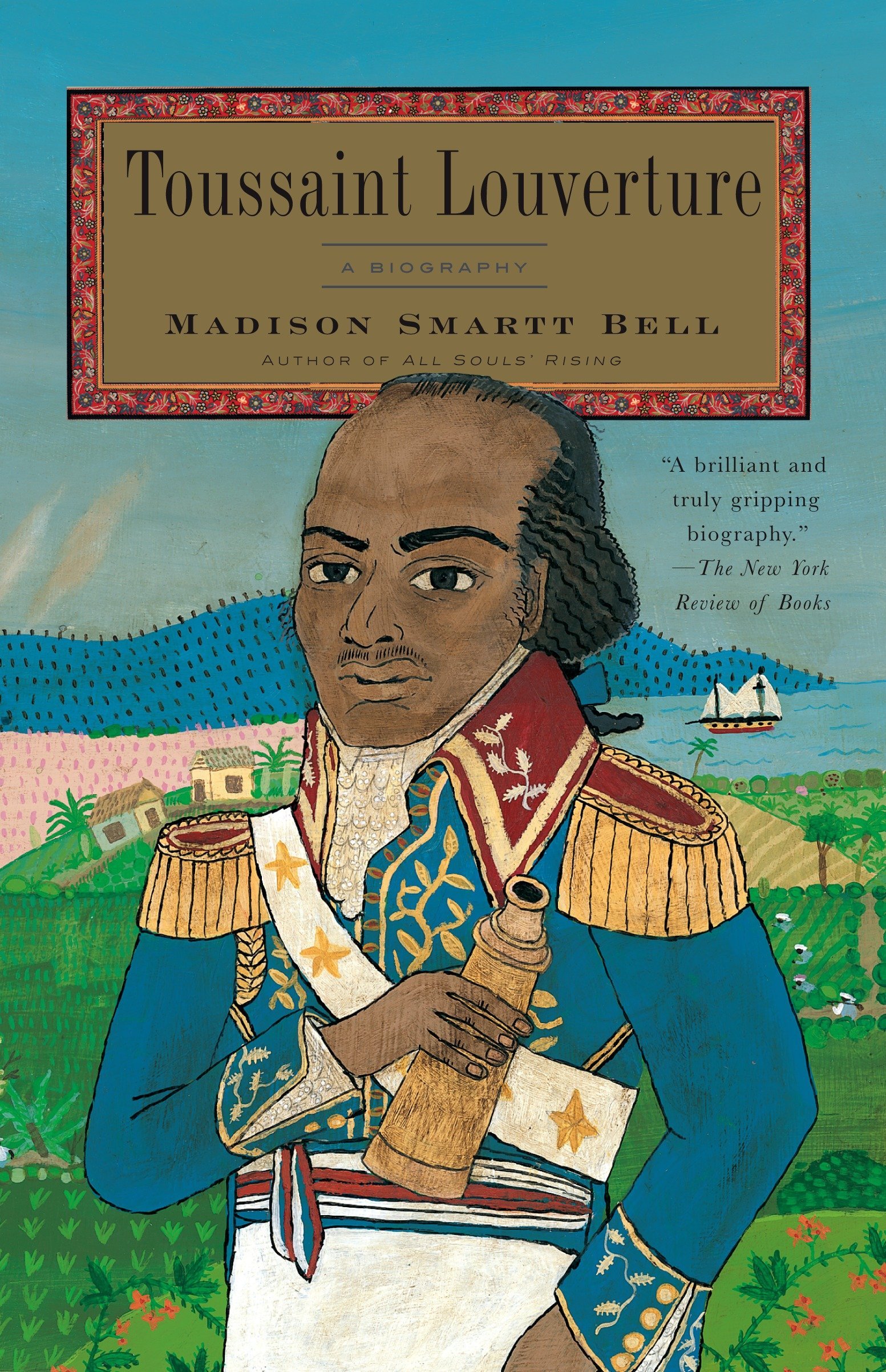

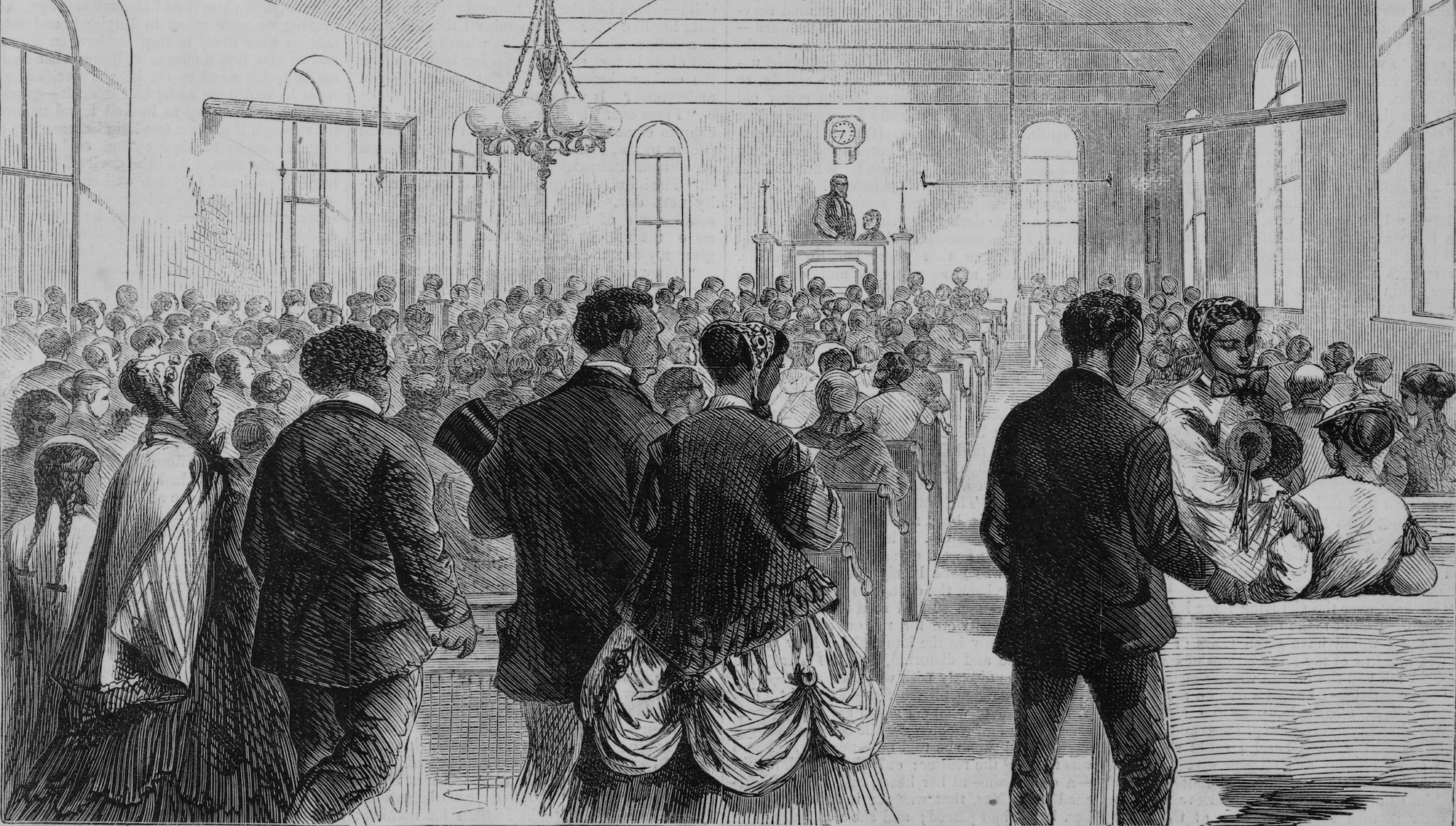

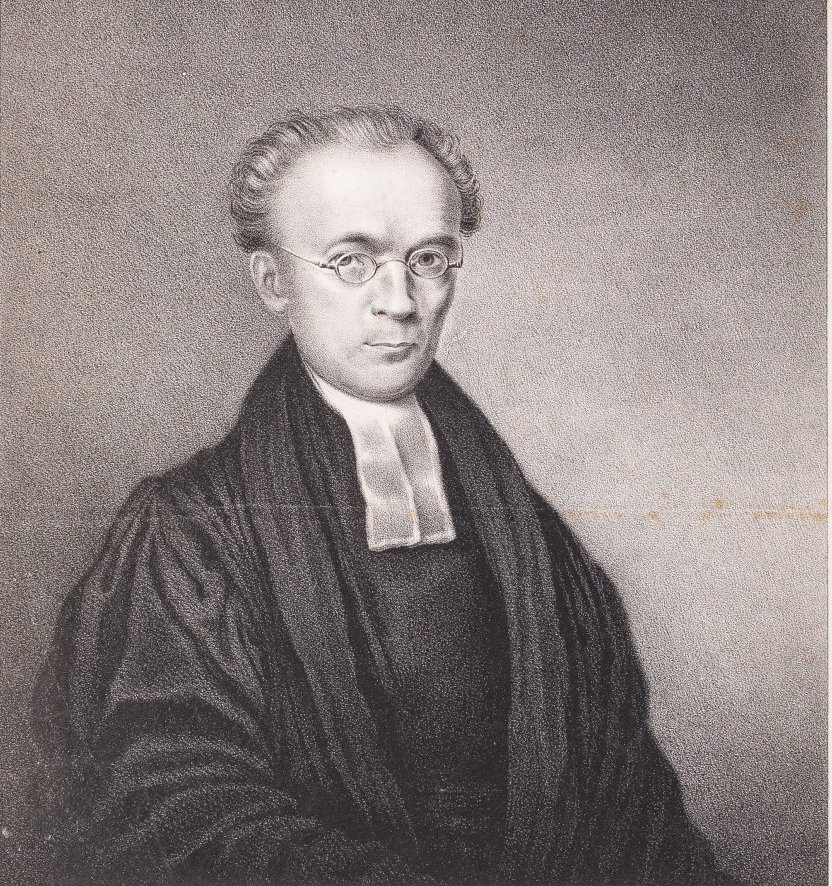

But none of the pairings I list above complement each other as well as the works of two Florida writers, one of the eighteenth and one of the twentieth century: William Bartram’s Travels and Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God. To begin with, the biographies of these two writers make for a fascinating comparison. Both approach their highly poetic and philosophical depictions of Florida with concrete backgrounds in the sciences: Hurston with her anthropology background and Bartram with his familial background in botany and naturalism. Both were single minded and wary of aligning themselves with grander political projects: Hurston was famously rebuffed by contemporary novelists like Richard Wright for refusing to take up the race issue, while Bartram turned down Jefferson’s invitation to join the Lewis and Clark expedition. Both were avid travelers, explorers, writers, gardeners, thinkers, and Florida enthusiasts.

Both authors write about nature as a lens to think metaphysically about human life. In other words, both Bartram and Hurston appear to be “watching God” through nature.

As a student of anthropology under Franz Boas and a lover of her home state of Florida, Hurston probably read Bartram’s Travels. Although no direct reference to these early American travelogues appears in her writing, she was certainly conscious of the tradition. In her autobiography, Dust Tracks on the Road, Hurston tells an anecdote she frames as the turning point of her education, when a teacher recited for the class the poem “Kubla Khan.” Her affection for that teacher, the drama of the reading, and the stunning imagery of the poem cemented her love of learning. This is the only specific reference that Hurston makes to the curriculum of her formal schooling, and one can only wonder if she recognized her native state of Florida in the imagery of the poem. The fact that Coleridge, in writing “Kubla Khan” (among other poems) took inspiration from Bartram’s travels down the St. John’s River is well documented in the poet’s notebooks.

Since Hurston was an innovator in bringing Southern black dialect into her fictional dialogue, diction is a natural focal point for literary study of her works. The same holds true for the study of William Bartram, not because of regional idiom so much as the pure foreignness of elevated eighteenth-century writing to the ears of contemporary adolescents. Look at how these two descriptive passages, because of their similar attitudes toward a storm, throw one another’s language nicely into relief. Hurston writes:

Ten feet higher and as far as they could see the muttering wall advanced before the braced-up waters like a roadcrusher on a cosmic scale. The monstropolous beast had left his bed. The two hundred miles an hour wind had loosed its chains. He seized hold of his dikes and ran forward until he met the quarters; uprooted them like grass and rushed on after his supposed to be conquerors, rolling the dikes, rolling the houses, rolling the people in houses along with other timbers. The sea was walking the earth with a heavy heel.